As part of my ongoing interest in mobile technology, I’ve been closely watching the wearables market and making use of many early products. From smart watches and glasses to fitness bands and clips, here’s what I’ve found to actually be valuable in wearable tech.

After many months of using different wearables, I stumbled upon a now obvious way of determining their value: do I keep them charged? Is a particular piece of hardware important enough to me that I go through the effort of keeping a charger around for it, track its battery life, and plug it in over and over again.

On more than one occasion, I had an even tougher test for my devices to pass: will I bother to get them replaced after they break? Over the past two years, I had two Fitbits and two Nike Fuelbands fail on me. I replaced the first, but not the second in both cases.

So what makes a wearable worth replacing or more importantly worth charging?

Meaningful Data Collection

Most fitness bands are built around the promise of collecting useful health-related information about you and your body. In practice, however they really turn out to be glorified pedometers. Collecting a rough approximation of the steps you take and inferring some kind of “activity” score. Though I initially found myself following (and even optimizing) this score, I quickly realized it lacked real meaning. As a result, getting 1,000 or 1,500 fuel points a day became less important over time.

Yet there is a lot of very meaningful health data wearables could collect. Nymi, for instance, tracks your cardiac rhythm. Google’s smart contacts lenses measure glucose levels in your tears. If that’s not enough, there’s wearable technologies for monitoring blood pressure, blood oxygen saturation, and more. This kind of data matters —especially to those with diabetes or heart conditions. Wearables that allow you track life or death metrics are very likely to stay charged.

Effortless Authentication

Today’s Internet is rife with passwords, usernames, and all their associated problems. Despite the many issues with Login experiences online, they remain the most popular way to authenticate and access our content on digital services. Wearables can change that.The Nymi band, mentioned earlier, actually doesn’t use your unique cardiac rhythm for health reasons. It makes use of your to heartbeat to authenticate your identity. Wearing a Nymi on your wrist potentially allows you to never enter another password again and instead rely on your vital signs to “wirelessly take control of your computer, your smartphone, your car and more.” Just be alive near your smartphone or PC, and you’re logged in.

Contextual Notifications

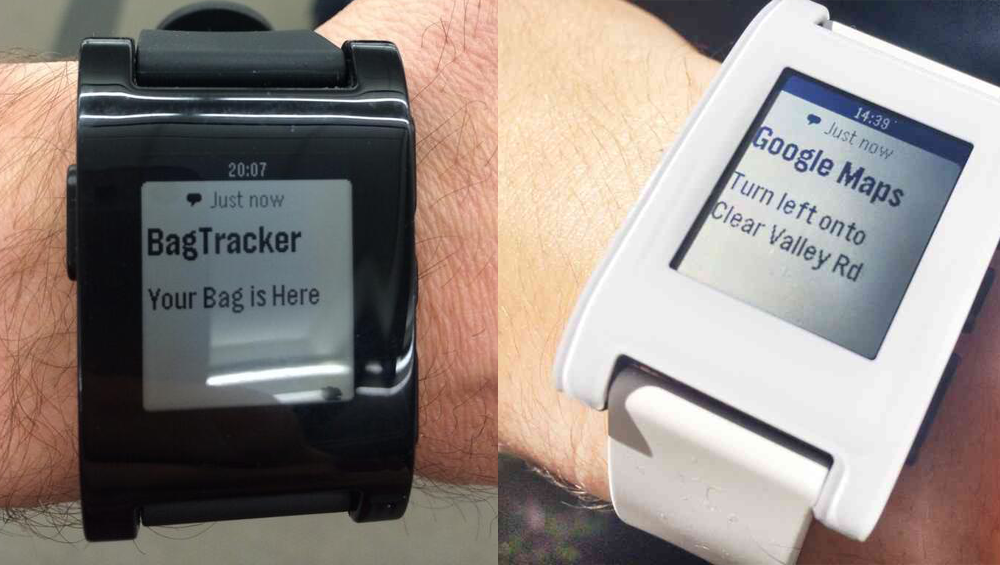

If you’re like me, you’ve got no shortage of buzzes and beeps competing for your attention. Notifications on my phone, my tablet, my PC, and now from my wrist and glasses frequently interrupt me with “important” information. When done wrong, these messages are an annoyance, when done right they’re the kind of thing that makes me keep my Pebble watch charged.So what makes a useful notification in the real world? Context. After paying for a coffee in Starbucks, my watch buzzes to tell me my remaining balance. While driving through an unfamiliar city, my wrist vibrates before upcoming turns. When my luggage arrives in baggage claim, a simple notification lets me know.

These notifications are not only useful but welcome. They give me timely bits of information that help me better understand the World around me and they do so in non-intrusive, almost ambient ways.

Faster Access?

There’s an endless amount of information on our phones. But getting to it requires pulling a pane of glass out of our pockets or purses and starting at it. Surely, there’s got to be a better way. Why not put the same information and actions on our wrists for faster, easier access to our apps?

That seems to be part of the thinking behind wearables like Google Glass, Android Wear, and Samsung’s Galaxy Gear: take what a smartphone can do and make it accessible with just a flick of the wrist or a nod of the head. It turns out that’s all it takes to see the current time on either of these devices. Everything else however, doesn’t pass the 30% better test that determines if people will switch their habits.

It’s not that much more convenient to take photos with your wrist or your face. And the tradeoffs for doing so are quite big: lower quality images, difficulty aiming, etc. This may be a temporary issue as wearable technology and (more importantly) the software that runs on it needs time to adapt to these new form factors.

But ultimately, I think wearables that try to replace the smartphone by shrinking it to fit on your wrist (or other body part) will struggle while those that complement our current set of devices and focus on the things they can do well will thrive. For me that means meaningful data collection, effortless authentication, and contextual notifications. As far as faster access goes... I guess we’ll have to find out as the next batch of wearable technology arrives on our wrists and beyond.